What if traditional Japanese elementary education got something right that we’re too quick to dismiss? We dive into the neuroscience behind old-school practices and discover why the brain craves both repetition and innovation, not one or the other.

We’d love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to share your comments!

“What we need is a transparent will that embraces the galaxy,

Great power and heat” Miyazawa Kenji

Profile

Yati Obara

Editor-in-Chief, Scientific Montessori

Based in Japan, born in 1989. Research Scientist at StudyX and Co-Director of the nonprofit think tank Polymath Research. Holds an M.Eng. and is an AMI-certified teacher. Focused on Montessori developmental theory and AI. Mother of two.

Hiro Obara

Publisher, Scientific Montessori

Based in Japan, born in 1990. CEO of StudyX and Co-Director of the nonprofit think tank Polymath Research. Works as a software developer and game designer. Father of two.

How Old-School Drills Light Up Young Minds

Hiro

I’ve been researching the brain and discovered something fascinating. Traditional Japanese elementary schools actually have habits that are surprisingly good for the brain.

Yati

What do you mean?

Hiro

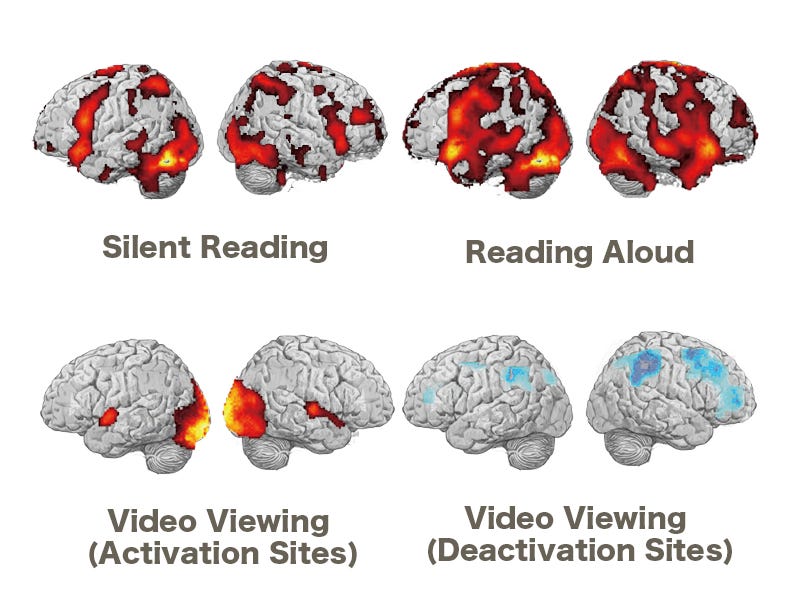

Take reading aloud, mental arithmetic, handwriting, especially writing characters beautifully and carefully. Brain imaging shows these activities create comprehensive neural activation. When they become habits, the prefrontal cortex develops. The elementary curriculum probably wasn’t designed with neuroscience in mind, yet it’s remarkably rational for brain development. Fascinating, right?

Yati

Montessori Elementary and other alternative approaches focus on children’s freedom and advanced content. Repetitive practice, reading, writing, arithmetic, gets dismissed as outdated, even unintelligent.

Hiro

Far from unintelligent, it’s brilliant. The brain develops through daily activation. Only habits create lasting change. Why? Synaptic circuits strengthen with frequent use. That’s basic neuroscience. Elementary schools function as social systems ensuring children regularly practice these brain-building activities: reading aloud, handwriting, calculating.

Yati

That makes sense.

Hiro

Brain training is like muscle training, no pain, no gain. Activation requires load, challenge, effort. I learned this developing a brain training app. People instinctively avoid mental strain. Consider this: cooking, walking, jogging, activities linked to longevity, all activate the brain. Yet forming these habits? That’s the hard part.

Yati

Guilty as charged. I skip the brain training exercises I’m bad at. Walking feels like a chore.

Hiro

Elementary education extends beyond the classroom. School transforms daily rhythms: early rising, breakfast, walking to school, greeting crossing guards, socializing with friends. These “non-cognitive” habits, they’re gold for brain development.

Yati

The research backs this up. Elderly people learning juggling increased brain plasticity (Boyke et al. 2008). Walking habits rejuvenated aging brains (Erickson et al. 2010). For children? Aerobic exercise boosted academic performance (Chaddock-Heyman et al. 2014).

Hiro

Very scientific. But here’s the flip side. Current schools are riddled with brain-hostile practices. Sitting for hours. Passive listening. Hands idle on desks. No wonder school refusal rates are skyrocketing, while there may be various reasons.

Yati

Look at Japanese school refusers’ daily routines. YouTube marathons. Gaming binges. Even learning center kids gravitate toward low-sensory, low-challenge activities. Minecraft. Coding. Comfortable, but not brain-building.

Hiro

That’s a serious problem for development. The root cause? Parents and learning center operators haven’t scientifically studied development. They confuse freedom with abandonment. Left to their own devices, literally, children disappear into digital worlds. Neglecting sensory experiences in the real world.

Yati

The research is terrifying. Internet-addicted children don’t just fail academically, their brain development halts (Takeuchi et al. 2018).

Hiro

It’s a cruel choice in Japan. If you avoid school, you have freedom, but smartphone, game, and internet addiction await. But if you go to school, you lack freedom, and unpleasant things like bullying, mental starvation, and military-style education await. International schools and alternative schools break through this dichotomy, but their tuition is ridiculously expensive. Currently, for most families, even if they wish for their children’s healthy development, their options are limited. So I think most people hope for reform in existing schools.

Yati

But reform faces resistance. The winners of the current system, those with prestigious degrees, comfortable lives, why would they want change? Their identity depends on the status quo.

Hiro

Right.

Yati

They’re myopic, maybe selfish. But can we blame them? The system trained them this way, compete, win, protect your position.

Hiro

True. The Japanese poet Miyazawa Kenji captured this perfectly in “An Outline of Peasant Art”. Let me read it here: “There can be no individual happiness until the whole world becomes happy. The consciousness of self evolves gradually from individual to collective society to universe.” What he wanted to say and the problems we’re sensing are similar. Essentially, our “consciousness is still small.”

Yati

People say education’s purpose is “to become happy.” Miyazawa Kenji ruined that simplicity for me. It’s the prisoner’s dilemma in action. Individual rational choices lead to Nash equilibrium, not Pareto optimality. Personal success doesn’t equal collective flourishing.

Hiro

I think intelligence is the spatiotemporal scale you can grasp, measured by predictive power. Like, sure, everyone can guess what’ll happen an hour from now, but a hundred years? That’s much harder. And if you keep stretching that to a thousand years, ten thousand years, a hundred million years, maybe that’s actually how we could think about developing intelligence in a more quantitative way. But then, how do you even do something that sounds like wizardry, or astrology, or alchemy? In the past, priests who served as advisors to kings had real power because they were skilled in astronomy and mathematics. They could predict things on Earth by reading the movements of the heavens, like nailing the timing of an eclipse, or changes in the seasons, or when snow or rain would come. And the reason they could do that was because they’d quietly been collecting data and working with hidden equations. There was always a trick behind it. But to ordinary people, farmers who had no education about the cosmos, it must have looked like magic, or some kind of divine oracle.

Yati

You’re always talking about these sci-fi kind of ideas, like what schools might be like a thousand years from now.

Hiro

Montessori Elementary curriculum centers on the history of the universe, Earth, and life, dealing cross-sectionally from macro to micro. Children learn the 13.8 billion year history of the universe, the 4.6 billion year history of Earth, and the 3.8 billion year history of life. That’s their foundation for predicting futures. Imagine the accuracy advantage.

Yati

Artificial intelligence follows the same principle. There’s a trend toward creating “smarter” AI by teaching it concepts that apply to larger spatiotemporal scales, like physics and mathematics, rather than just training it on internet data. This leads to more accurate predictions.

Hiro

These days, science and technology have given us access to massive amounts of historical data. But there’s still so much we don’t fully understand in fields like planetary science, geology, and archaeology. Huge parts of the record are still literally buried underground. And once we dig that up and start reflecting it in our knowledge, everything shifts. Academic systems, educational frameworks, all of it will need to be updated. And sometimes that means we’ll have to admit, “what we thought was true was actually wrong.” It’s like when people moved from believing in the geocentric model to adopting the heliocentric one. We should expect those kinds of Copernican revolutions. Knowledge is always moving. That’s why we need educational systems that can stay strong and flexible through constant change.

Yati

These revolutions are happening all the time, in big ways and small. Some people don’t wait for society to catch up. They bring these radical new truths into their daily lives before the rest of us even notice. Quite a few are already living through their own personal Copernican revolutions. The future is already here. It just hasn’t reached everyone yet.

Hiro

Montessori education itself isn’t mainstream in Japan yet. While some countries have made it public education, in Japan, there are almost no private schools offering it. With the declining birthrate and aging population, it’s easy to predict that establishing new schools using traditional school management models will be financially difficult. But since Montessori education is clearly superior in quality to existing education, I personally want to somehow bring it to standardization.

Yati

So we’re ignoring existing models entirely. We’re physically designing a new model from scratch. We’ve launched our experimental alternative school April 2025.

Hiro

Exactly. The school has a new model. The model is distributed, not centralized, and mobile. I think mobile is cosmic. We’ll discuss the details another time. At the societal level, it’s important to increase experiments with these new alternative models, even if they’re small. I think it’s important to regularly increase learning density, deepen education in the right direction, and actively try new things.

Yati

The brain research I cited earlier also says that acquiring new skills activates the prefrontal cortex.

Hiro

Sure, individual prefrontal development matters. But I think we also need to talk about something bigger, like the prefrontal cortex of society, maybe even of the universe. Between the ages of six and twelve, imagination really expands. That’s when independent thinking starts to emerge, and that’s crucial. Elementary school, at the very least, should train kids for that shift. Current schools do help kids build some healthy brain habits. That’s good and worth keeping. But we also need to move to the next stage, where the brain isn’t just active, it’s used more purposefully.

Yati

That’s why at our alternative school, Polymath School of Morioka, we emphasize both brain development support and Montessori-style cosmic education. There’s no other school with such good balance. Plus, it’s free without tax funding. [laughs]

Hiro

That’s right. We’re aiming to be “the most intellectual school on Earth.” [laughs]